DAY 684.1 | The Nazi Persecution of Homosexuals

Die Männer mit dem rosa Winkel

We might view the Nazis' execution of their anti-homosexual policies as an integral step in putting into practice the ideology of social purification that ultimately led to the annihilation of six million Jews. The measures taken against the homosexual subculture and the homosexual movement in the first four years of the Hitler regime aided the Nazis in establishing a technology and bureaucracy of mass stigmatization, isolation, and persecution against a comparatively small, fragmented, and ill-defined social group that was already the object of popular prejudice and whose persecution attracted no criticism whatsoever from foreign powers or traditionalist factions within the German government.

Each of the methods initially deployed against homosexuals between 1933 and 1936 – including the destruction of cultural and social territories and networks, the silencing of means of communication, the consignment of a despised group to concentration camps, and the application of state-sponsored mass murder – would be carried to systematic elaboration in the Holocaust against European Jewry. The ends of the Nazi persecution of homosexuals and the genocide of the Jews differed considerably, but the historical development of the means was thus intrinsically connected. (1)

Before the storm

In 1898, Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld circulated a petition to abolish Paragraph 175 (criminalizing homosexuality). He obtained the signatures of prominent writers, lawyers, politicians, and church dignitaries. The petition was discussed in the Reichstag and rejected. Only the Social Democratic Party, under the guidance of August Bebel, pleaded the reform. Most deputies were outraged and did not hide their abhorrence.

All the old arguments of the past were marshaled: homosexuality corrupts a nation; it breaks the moral fiber of the citizens; it is un-Germanic; it is connected with dangerously corrosive left-wing and Jewish elements (this from the right), or it is typical of the dissolute aristocracy and high bourgeoisie (this from the left). Above all, the spread of homosexual behavior would lead to Germany's decline, just as it has always spearheaded the ruin of great empires. Such arguments, recycled and sometimes imbued with Himmler's special brand of crackpot fanaticism, would later reappear in numerous Nazi directives.

Despite the setback in 1898, Hirschfeld refused to give up. Soon afterwards, he issued one of his many pleas for understanding, an appeal entitled What People Should Know about the Third Sex. By the outbreak of WWI, more than 50,000 copies had been distributed. Hirschfeld's tireless efforts, while in many respects enlightened, nevertheless did much to establish the notion of homosexuals as a medically defined, vulnerable, and official minority.

Like many turn-of-the-century psychiatrists, he wanted legal punishment to be replaced by treatment of patients who deserved to be pitied and helped rather than censured and ignored. He followed the conventions of his time when he sought the key to homosexuality by measuring the circumferences of male pelvises and chests in an attempt to define a physiologically recognizable "third sex."

Only after the Nazis had turned his lifework into ashes did he concede that, on the one hand, he had failed to prove that homosexuals were characterized by distinct and measurable biological and physiological qualities and that, on the other hand, he had unwittingly deepened popular prejudices by endowing male homosexuals with "feminine" characteristics. This had only served to confirm the prevailing assumption that because homosexuals were "not really men," they were therefore inferior.

The notion of homosexuals as "basically different" permitted the left as well as the right to revile them whenever it was politically expedient to do so. The very word homosexual could be used as an epithet and a term of opprobrium. (2)

The promise of a progressive change

From the 1880's into the Nazi era, religious organizations similarly waged a concerted "moral purity" campaign against phenomena which they regarded as urban vice and decadence – abortion, prostitution, sexually-oriented publications and amusements, women working outside the home, homosexual relations – in short, the signs of changing gender and social structures characteristic of modern life. The most prominent of these efforts were associated with the Inner Mission, the national Protestant social welfare organization, which distributed tracts, set up youth groups, lobbied against legal reform, and advocated castration of sex offenders.

Despite such attempts at regulation, the subcultures of homosexual men and women continued developing – albeit in a fairly precarious form – in the years before World War I. This development was grounded in two broader social shifts: 1) the emergence of sexuality in general into the public and more specifically the commercial sphere; and 2) the movement of women into factory work and into the rapidly expanding secretarial field – a movement that for the first time offered personal independence to significant numbers of working- and middle-class women.

After the turn of the century, sexual, social, and intellectual territories for homosexual men and women were expanding to include cafés and pastry shops, beer cellars, nightclubs, bath houses, bookstores, sports and hobby clubs, small hotels, apartment buildings and sections of neighborhoods. In some cases, these were mixed settings where the greeting ranged from toleration to genuine welcome; in others, they were specifically homosexual milieus, often run by entrepreneurs who were themselves homosexual. By 1914, Berlin alone had an estimated 40 homosexual bars – including a number catering particularly to lesbians – several homosexual periodicals, and one- to two-thousand male prostitutes. By the early 1920's, similar developments on a smaller scale had appeared in other German cities.

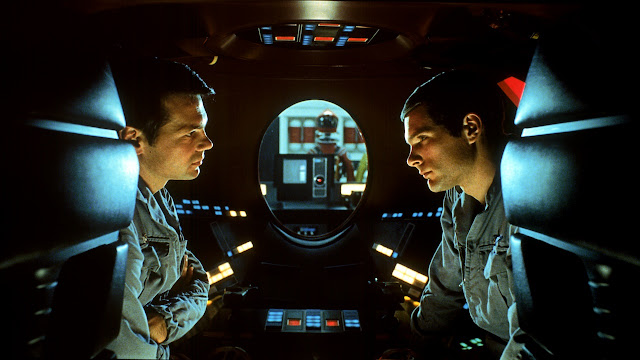

For homosexuals whose primary experience had been isolation and confusion, the discovery of urban queer life could be a revelation. To quote from one contemporary observer, Magnus Hirschfeld "Uranians have been seen arriving from the depths of the provinces weeping tears of joy at the sight of this spectacle." The sense many homosexuals shared about Berlin was reflected in the name of the German capital's most famous queer nightclub of the 1920s and early 1930s, where the art déco neon signs spelled out "Eldorado" (pictured) – recalling the mythic land of gold which the Conquistadors had sought in vain. And to make sure no that one missed the point, two large signs over the main entrance announced: "You've found it!"

Efforts to organize German homosexuals politically emerged in tandem with the profound social changes that we have just been considering. For homosexual men, this struggle developed primarily as a specific movement to reverse the medical discourse of the homosexual personality type into a depathologized "homosexual identity" worthy of social equality.

The period of social change that gave rise to the homosexual subculture, the homosexual rights movement, the women's movement, and the "life improvement movement" in general also provoked strong conservative reactions in Germany – with attendant calls for strict regulation of sexual, political, ethnic, and religious minorities. World War I, which resulted in the deaths of nearly two million German soldiers and an economically ruinous defeat, exacerbated these tensions and polarities.

The period of social change that gave rise to the homosexual subculture, the homosexual rights movement, the women's movement, and the "life improvement movement" in general also provoked strong conservative reactions in Germany – with attendant calls for strict regulation of sexual, political, ethnic, and religious minorities. World War I, which resulted in the deaths of nearly two million German soldiers and an economically ruinous defeat, exacerbated these tensions and polarities.

The establishment of the democratic Weimar Republic – which replaced the Imperial regime in 1918 – initially appeared to promise progressive change, but hopes for continuing reform disappeared as economic conditions in Germany deteriorated. A hyper-inflation in 1922-1923 – followed by the worldwide economic crash in 1929 – added massive unemployment to the disruptions produced by the war. In these circumstances of deepening economic crisis and social conflict, reactionary political discourses of anti-socialism, anti-semitism, xenophobia, and homophobia rapidly gained ground.

Among the organizations promoting right-wing ideology of this sort were the National Socialists. Founded in 1920 with the merging of several smaller right-wing extremist groups, the Nazi Party played an increasingly visible and aggressive role as the decade progressed, attracting adherents from the masses of Germans seeking drastic solutions to the upheavals of the era. The Sturmabteilung or "Storm Section" of the Party – known by its German acronym as the SA – directly recruited unemployed young men, providing them with uniforms, meals, and a sense of belonging, while deploying them in paramilitary gangs to enforce terror against political opponents and minority groups.

The Nazis and their sympathizers immediately ranked homosexuals among the groups supposedly at fault for the instability of German society and the weakness of the German state. As a Jew, a leftist, a social reformer and a homosexual organizer, Magnus Hirschfeld was an early target. In 1921, Hirschfeld stood up to hecklers while giving a lecture in Munich, the city that was ground zero of the right-wing extremist movement. (1)

Nazi Germany: Denunciations, arrests and convictions

The police work of tracking down suspected homosexuals depended largely on denunciations from ordinary citizens. Nazi propaganda that labeled homosexuals "antisocial parasites" and "enemies of the state" inflamed already existing prejudices. Citizens turned in men, often on the flimsiest evidence, for as many reasons as there were denunciations. Reflecting on the dramatic rise of legal proceedings against homosexuals since 1933, Josef Meisinger of the Reich Central Office for Combating Homosexuality and Abortion proudly remarked in April 1937: "We must naturally also take into account the greater public readiness to report [homosexuals] as a result of National Socialist education."

Acting on the basis of these informants, the Gestapo and Criminal Police arbitrarily seized and questioned suspects as well as possible corroborating witnesses. Those denounced were often forced to give up names of friends and acquaintances, thereby becoming informants themselves. Where criminal proceedings once required a proved act, now a suggestive accusation sufficed.

During the Nazi era, some 100,000 men were arrested on violations of Paragraph 175. Of these, nearly 78,000 were arrested during the three years between Heinrich Himmler's appointment as chief of German police in 1936 and the outbreak of World War II in 1939. The Gestapo and Criminal Police worked in tandem, occasionally in massive sweeps but more often as follow–up to individual denunciations.

Most victims were from the working class. Less able to afford private apartments or homes, they found partners in semi–public places that put them at greater risk of discovery, including by police entrapment.

As reports of the massive arrests spread, mostly by word of mouth, a pervasive atmosphere of fear enveloped Germany's homosexuals. Just as the state desired, the physical repression of a minority of homosexual men served to limit activities of the vast majority.

Of the estimated 100,000 men arrested under Paragraph 175 between 1933 and 1945, half were convicted of violating the law. Just as arrests rose precipitously after the 1935 revision of Paragraph 175, so, too, did conviction rates, reaching more than ten times those of the last years of the Weimar Republic and peaking at more than 8,500 in 1938. Prison sentences, the most common punishment in the Nazi persecution of homosexuals, varied with the sexual act involved and the individual's prior history.

For many, imprisonment meant hard labor, part of the Nazi "re–education" program. Conditions in German prisons, penitentiaries, and penal camps were notoriously wretched, and those incarcerated under Paragraph 175 faced both the brutality of the guards and the hatred of their fellow inmates.

In a small number of cases, medical experts testified that some homosexuality constituted a serious mental illness and danger to society. Under Paragraph 42b of the Reich Criminal Code, some men were institutionalized, a fate that could have disastrous consequences (including death) during the war. (3)

The stepping up of prosecutions

With the support of new legal definitions of crime, a tightly knit national police and security apparatus, and a public opinion manipulated by propaganda and demagogy, the rate of prosecutions greatly increased after 1936. Whereas just a thousand people were convicted in 1934, there were already 5,310 in 1936.

Two years later, the statistics referred to 8,562 legally valid convictions. The police and prosecution departments, in the words of a regular commentary on crime figures, acted 'with ever growing vigour' against 'these moral aberrations which are so harmful to the strength of the Volk. And Prosecutor-General Wagner stressed what one could not have expected to be otherwise after all the investment in propaganda and police searches: 'the public, through its increased level of reporting, also [supports...] the fight against these offenses. Broadly speaking, no more homosexual acts were committed [ ...] than before, but they were recorded and prosecuted on a much larger scale than before.

Two years later, the statistics referred to 8,562 legally valid convictions. The police and prosecution departments, in the words of a regular commentary on crime figures, acted 'with ever growing vigour' against 'these moral aberrations which are so harmful to the strength of the Volk. And Prosecutor-General Wagner stressed what one could not have expected to be otherwise after all the investment in propaganda and police searches: 'the public, through its increased level of reporting, also [supports...] the fight against these offenses. Broadly speaking, no more homosexual acts were committed [ ...] than before, but they were recorded and prosecuted on a much larger scale than before.

Whereas between 1931 and 1933 a total of 2,319 persons were put on trial and found guilty of offences under Paragraph l75 of the Penal Code, this figure rose nearly tenfold in the first three years after the tougher redefinition of offenses. In the years from 1936 to 1938 the number convicted came to 22,143. No reliable data are available for the war years after 1943, so that the total number of convictions for homosexuality in the 'Third Reich' can only be estimated - roughly 50,000 men according to Wuttke. But the Gestapo or the Reich Office had considerably more on record as suspects or as presumed partners. Between 1937 and 1940 there were more than 90,000 men and youths.

Alongside this numerical increase there was also a qualitative toughening of prosecution policy. After 1933 the number of acquittals continually declined and by 1936 was down to a mere quarter of the figure for 1918 (the year with the most verdicts of 'not guilty'). The same trend is apparent in the fines handed down by courts, in comparison with which there was a marked increase in sentences of imprisonment or penal servitude. Men with previous convictions were treated with particular severity - above all so-called corrupters of youth, but also young men considered to be 'rentboys'.

At the instigation of the Reich Office special mobile units of the Gestapo carried out operations in a number of towns. The reasons could be quite varied: from the eradication of 'centres of the epidemic' in day or boarding schools to denunciations with a real or alleged political background.

There is no evidence of a sudden nationwide 'clampdown' comparable to the attacks on Jews in the pogrom night of 1938. But the offensive was certainly coordinated in a number of ways. This was particularly true of actions with a clear political motivation: e.g., the arrests of thousands of priests, religions brothers and lay persons during the staged 'cloister trials' against the Catholic Church or the targeting of the activities of the Bund Youth that had already been banned in 1934, where special prominence was given to the trial of the Nerother Wandervogel in 1936.

The ultimately arbitrary nature of the Nazis' practice, especially that of Heinrich Himmler as architect of their anti-homosexual policy, is illustrated by the special regulation approved in October 1937 for actors and artists. Under the pretext of 'Reichization'- that is, of applying uniform norms throughout the Reich - the rules on preventive detention and police supervision that had been issued three years before were made tougher still at the end of 1937.

Now anyone who fitted the completely arbitrary criteria for an 'experienced' or 'habitual' male homosexual had to reckon that, after serving his term of imprisonment or penal servitude, he would be deported for 're-education' in a concentration camp. (4)

Homosexuals in Hitler's concentration camps

When the German concentration camps were thrown open in 1945, a wave of terror swept over Germany and the entire world. But the indignation, pity and horror soon were wiped out by the general misery that followed the war, by daily worries about finding food and a place to live.

The Dachau trials remained unknown to large parts of the public, and it didn't take long before some individuals started to show signs of doubt about the genuine gravity of the horrors that took place in the camps. Too many people had a powerful interest in minimizing the atrocities that had been committed and in letting them fall into obscurity as quickly as possible.

A few books did appear, but they were not always objective, and often they were aimed at sensationalism. As for the survivors of the horrors of the camps, they were busy trying to find their place in the new society then being formed -- a society that they hoped would be in keeping with fundamental humanitarian principles. From time to time, organizations representing the interests of the victims -- particularly Jews, who were the most severely affected, as well as communists, socialists and displaced foreigners -- tried to claim indemnification, most often without much success.

The Dachau trials remained unknown to large parts of the public, and it didn't take long before some individuals started to show signs of doubt about the genuine gravity of the horrors that took place in the camps. Too many people had a powerful interest in minimizing the atrocities that had been committed and in letting them fall into obscurity as quickly as possible.

A few books did appear, but they were not always objective, and often they were aimed at sensationalism. As for the survivors of the horrors of the camps, they were busy trying to find their place in the new society then being formed -- a society that they hoped would be in keeping with fundamental humanitarian principles. From time to time, organizations representing the interests of the victims -- particularly Jews, who were the most severely affected, as well as communists, socialists and displaced foreigners -- tried to claim indemnification, most often without much success.

The common law prisoners -- pimps, killers and professional thieves who had been so numerous in the camps and who had at first greatly damaged the reputations of the liberated internees -- quickly rediscovered their old lives and disappeared from view. Bonds of friendship already had been less than firm in the camps, where shared misery too often brought out the basest instincts; such bonds rapidly came undone. The recent trials of former concentration camp doctors have created barely even a weak renewal of curiosity and interest regarding these past events.

Yet there is one group among all the victims that has never received the light of publicity, hasn't complained about the damage it sustained, and hasn't encountered any understanding from the newspapers, from government agencies or from organizations that defend the interests of former internees: That group is the homophiles [homosexuals]. Because Paragraph 175 of the German Penal Code -- the very Paragraph 175 that has been a subject of debate for decades -- makes homophiles into criminals, they encounter no pity from the public, and of course can make no claim for damages. To this day, no one has sought to learn how many homophiles were hunted down by the Nazis, nor to learn what the survivors retrieved of their lives and their belongings.

The trials of former camp doctors have recently [published in 1960] called to mind the fact that thousands of homophiles were forcibly castrated, often under beastly conditions. In the camps, homophiles often were singled out for special mistreatment. The author of these lines himself once witnessed how an effeminate young man had to dance repeatedly in front of the SS, only to be subsequently strung up on a beam in the guardroom with his hands and feet tied, then beaten horribly. The author also recalls the "latrine parades" in one of the first camps (Sonnenburg), for which the commandant always chose homophiles.

We must not forget that the homophiles in question often were honorable and cultured citizens who held important positions in society and in the government. During the seven years that he passed in various camps, the author of this article got to know a Prussian prince, major athletes, professors, schoolteachers, engineers, artisans, workers of every type -- and naturally, prostitutes, as well.

Certainly, not all of them were worthwhile people, but the majority were completely lost and alone in the world of the concentration camps. During their rare hours of leisure, they lived largely in isolation. It was thus that I came to know the tragedy of a very civilized foreign embassy attaché who remained absolutely walled-up and unapproachable in a boundless and inescapable despair. He couldn't manage to make sense of the atrocious cruelty that he saw around him, and one day, for no apparent reason, he slumped over dead.

To this day, I find it impossible to recall all those comrades, those outrages, those deaths without sinking into profound despair.

None of this would have been possible without the legal opportunities that Paragraph 175 offered to the sadistic butchers of the Third Reich. I am now an old man. In my youth, I knew the activities and the struggles of the homophile circles that were then united under Magnus Hirschfeld, Adolf Brand, Fritz Radszuweit and others -- men who gave their honorable names to the fight for rights. I worked with them and I joined them in hoping for understanding and justice.

Whether Paragraph 175 is maintained or repealed is no longer of much concern to me personally. But I hope for all those human beings known or unknown who still live under the weight of its constant threat that -- despite everything -- reason, progress, science and the courage of the medical profession will finally win the day. If that happens, the victims of all the concentration camps will not have died in vain. (5)

Arrival at Sachsenhausen

By January 1940 the complement for the transport was made up, and we were to be taken to a camp. One night we were loaded thirty to forty at a time into the police wagons, and driven to a freight station where a prison train was already waiting. This train consisted mainly of cattle trucks with heavily barred open windows, as well as so-called cell wagons. These were also cattle trucks, but divided up into five or six cells, similarly barred, and set aside for the worst criminals.

I was placed in one of these cells, together with two young men of about my age. We remained together the whole journey. This lasted thirteen days, and proceeded via Salzburg, Munich, Frankfurt, and Leipzig to Berlin-Oranienburg. Each evening we were put off the train and taken to a prison to spend the night, sometimes by truck, but other times on foot. If we went on foot, we had to march in long heavy chains. These gave a ghostly rattle, like a slave caravan in the depths of the Middle Ages, and passersby would stare fixedly at us in terror.

The cells in the cell wagon only had proper room for one person, with a wooden table and bench. That was the entire furniture, not even a water jug or chamber pot. We were fed only in the evening, at the prisons where we stopped overnight, aslo being given there a large piece of bread to take on the train the next day. If the train was to stay clean, then we could only attend to the wants of nature at night [...]

I was placed in one of these cells, together with two young men of about my age. We remained together the whole journey. This lasted thirteen days, and proceeded via Salzburg, Munich, Frankfurt, and Leipzig to Berlin-Oranienburg. Each evening we were put off the train and taken to a prison to spend the night, sometimes by truck, but other times on foot. If we went on foot, we had to march in long heavy chains. These gave a ghostly rattle, like a slave caravan in the depths of the Middle Ages, and passersby would stare fixedly at us in terror.

The cells in the cell wagon only had proper room for one person, with a wooden table and bench. That was the entire furniture, not even a water jug or chamber pot. We were fed only in the evening, at the prisons where we stopped overnight, aslo being given there a large piece of bread to take on the train the next day. If the train was to stay clean, then we could only attend to the wants of nature at night [...]

When we reached the Oranienburg station, we were again loaded up a ramp onto trucks and driven to Sachsenhausen camp [...] As soon as we were unloaded on the large, open parade ground, some SS NCOs came along and attacked us with sticks. We had to form up in rows of five, and it took quite a while, and many blows and insults, before our terrified ranks were assembled. Then we had a roll call, having to step forward and repeat our name and offense, whereupon we were immediately handed over to our particular block leader.

When my name was called I stepped forward, gave my name, and mentioned Paragraph 175. With the words. "You filthy queer, get over there, you butt-fucker!" I received several kicks from behind and was kicked over to an SS sergeant who had charge of my block. The first thing I got from him was a violent blow on my face that threw me to the ground. I pulled myself up and respectfully stood before him, whereupon he brought his knee up hard into my groin so that I doubled up with pain on the ground. Some prisoners who were on duty immediately called out to me. "Stand up quick, otherwise he'll kick you to bits!" My face still twisted, I stood up again in front of my block sergeant, who grinned at me and said: "That was your entrance fee, you filthy Viennese swine, so that you know who your block leader is."

When the whole transport was finally divided up, there were about twenty men in our category. We were driven to our block at the double, interrupted by the commands: "Lie down! Stand up! Lie down, stand up!" and so on, from the block leader and some of his men, then having once again to form up in ranks of three. We then had to strip completely naked, lay our clothes on the ground in front of us, with shoes and socks on top, and wait - wait - wait. It was January and a few degrees below zero, with an icy wind blowing through the camp, yet we were left naked and barefoot on the snow-covered ground, to stand and wait. An SS corporal in winter coat with fur collar strode through our ranks and struck now one of us, now another, with a horsewhip, crying. "This is so you don't make me feel cold, you filthy queers." He also trod deliberately on the prisoners' toes with his heavy boots, making them cry out in pain. Anyone who made a sound, however, was immediately punched in the stomach with the butt end of his whip with a force that took his breath away. Almost sweating from dealing out blows up and down, the SS corporal said, "You queers are going to remain here until you cool off."*

Finally, after a terribly long time, we were allowed to march to the showers - still naked and barefoot. Our clothes, which had already had nametags put in, remained behind, and had vanished when we returned. We had to wash ourselves in cold water, and some of the new arrivals collapsed with cold and exhaustion. Only then did the camp doctor have the warrn water turned on, so that we could thaw ourselves out. After the shower we were taken to the next room, where we had to cut our hair, pubic hair included. Finally we were taken, still naked - to the clothing stores, where we were given underwear and were "fitted" with prison clothing.'This was distributed quite irrespective of size. The trousers I received were far too short, and came only just below my calves; the jacket was much too narrow and had too-short sleeves. Only the coat fitted tolerably well, but by mere accident. The shoes were a little too big and smelled strongly of sweat, but they had leather soles, which made walking a lot easier than the wooden soled shoes that many new arrivals received. As far as clothing went, at least, I didn't do too badly. Then we had to form up again outside our block and have its organization explained to us by the camp commander. Our block was occupied only by homosexuals, with about 250 men in each wing. We could only sleep in our nightshirts, and had to keep our hands outside the blankets, for: "You queer assholes aren't going to start jerking off here!" The windows had a centimeter of ice on them. Anyone found with his underclothes on in bed or his hands under his blanket - there were checks almost every night - was taken outside and had several bowls of water poured over him before being left standing outside for a good hour. Only a few people survived this treatment. The least result was bronchitis, and it was rare for any gay person taken into the sick bay to come out alive. We who wore the pink triangle were prioritized for medical experiments, and these generally ended in death. For my part, therefore, I took every care I could not to offend against the regulations.

Our block senior and his aides were "greens" - that is, criminals. They looked it, and behaved like it too. Brutal and merciless toward us "queers," and concerned only with their own privilege and advantage, they were as much feared by us as the SS. In Sachsenhausen, at least, a homosexual was never permitted to have any position of responsibility. Nor could we even speak with prisoners from other blocks, with a different-colored badge; we were told we might try to seduce them. And yet homosexuality was much more rife in the other blocks, where there were no men with the pink triangle, than it was in our own. We were also forbidden to approach nearer than five meters of the other blocks. Anyone caught doing so was whipped on the "horse," and was sure of at least fifteen to twenty strokes. Other categories of prisoner were similarly forbidden to enter our block. We were to remain isolated as the damnedest of the damned, the camp's "shitty queers," condemned to liquidation and helpless prey to all the torments inflicted by the SS and the Kapos.

The day regularly began at 6 a.m., or 5 a.m. in summer, and in just half an hour we had to be washed, dressed, and have our beds made in the military style. If you still had time, you could have breakfast, which meant hurriedly slurping down the thin flour soup, hot or lukewarm, and eating your piece of bread. Then we had to form up in eights on the parade ground for morning roll call. Work followed, in winter from 7-30 a.m. to 5 p.m., and in summer from 7 a.m. to 8 p.m., with a half-hour break at the workplace. After work, straight back to the camp and immediate parade for evening roll call. Each block marched in formation to the parade ground and had its permanent position there. The morning parade was not so drawn out as the much-feared evening roll call, for only the block numbers were counted, which took about an hour, and then the command was given for work detachments to form up.

At every parade, those who had just died had also to be present; that is, they were laid out at the end of each block and counted as well. Only after the parade, having been tallied by the report officer, were they taken to the mortuary and subsequently burned.Disabled prisoners had also to be present for parade. Time and again we helped or carried comrades to the parade ground who had been beaten by the SS only hours before. Or we had to bring along fellow prisoners who were half-frozen or feverish, so as to have our numbers complete. Any man missing from our block meant many blows and thus further deaths. We new arrivals were now assigned to our work, which was to keep the area around the block clean. That at least is what we were told by the NCO in charge. In reality, the purpose was to break the very last spark of independent spirit that might possibly remain in the new prisoners, by senseless yet very heavy labor, and to destroy the little human dignity that we still retained. This work continued until a new batch of pink-triangle prisoners were delivered to our block and we were replaced. Our work, then, was as follows: in the moming we had to cart the snow outside our block from the left side of the road to the right side. In the aftemoon we had to cart the same snow back from the right side to the left. We didn't have barrows and shovels to perform this work either - that would have been far too simple for us "queers." No, our SS masters had thought up something much better. We had to put on our coats with the buttoned side backward, and take the snow away in the container this provided. We had to shovel up the snow with our hands - our bare hands, as we didn't have any gloves. We worked in teams of two. Twenty turns at shoveling up the snow with our hands, then twenty turns at carrying it away. And so right through to the evening, and all at the double! This mental and bodily torment lasted six days, until at last new pink-triangle prisoners were delivered to our block and took over from us. Our hands were cracked all over and half frozen off, and we had become dumb and indifferent slaves of the SS. I learned from prisoners who had already been in our block a good while that in summer similar work was done with earth and sand. Above the gate of the prison camp, however, the "meaningful" Nazi slogan was written in big capitals. "Freedom through work! [Arbeit Macht Frei]"

*The slang word for homosexual used here is "warmer Bruder", literally "hot brother", which gives occasion for a lot of vicious puns. (6)

Sources :

(1) From Eldorado to the Third Reich, The Life & Death of a Homosexual Culture, lecture by Gerard Koskovich, given at the Multicultural Center of the University of California, Santa Barbara, October 28, 1997. Copyright © 1997 Ray Gerard Koskovich.

(2) The Pink Triangle, Richard Plant, Henry Holt and Company, Inc., 1986.

(3) United States Holocaust Memorial Online Exhibition

(4) Hidden Holocaust ?, Günter Grau, Cassell, 1995. Translated from German by Patrick Camiller.

(5) Les homophiles dans les camps de concentration d'Hitler, B. M., "Die Runde" (Bert Micha), Arcadie, no. 82 (octobre 1960), p. 616-618. Translated from the French by Gerard Koskovich.

(6) The Men with the Pink Triangle, Heinz Heger (alias), translated by David Fernbach, Alyson Books, 1980

Photos:

- Disused electrified fence, Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp (Copyright © MNC)

- Eldorado gay bar, Berlin (1920s - 1933)

- Entrance, Administration unit, Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp (Copyright © MNC)

- Entrance, Administration unit, Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp (Copyright © MNC)

- Entrance gate to Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp, with the motto "Arbeit Macht Frei" (Work sets you free). Copyright © MNC

- Nollendorfplatz Memorial to Homosexual Victims of Nazism, Berlin. (Copyright © MNC)

- "Death Strip" surrounding Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp (Copyright © MNC)

Disclaimer

If you are the copyright owner of a photograph, video, artwork, text posted to this nonprofit blog and want it removed or credited, please do not hesitate to contact me at mynarrowcorner@gmail.com

and the item(s) will be promptly taken down or credited. Thank you.

Deutschlands Schande :(

ReplyDeleteToday there are sick reactionary forces in the world that would go back to this lunacy, in the Mid-East, Africa, Asia, Europe and USA.

(vvs)

👍

DeleteThis is an important read for all. I hope many reference it and pass it on. We should never forget the brutality that was but should never have been. thank you for this post- it is difficult but so important to remember.

DeleteI would add, if I may, that as all this was happening homosexuality still prevailed all throughout the German society and indeed military- just more discretely (so being gay was not a defect nor a disease but a natural occurrence; ie. the leader of the SA was openly gay and accepted by Hitler- he was executed not for being gay but for becoming a rival/too big, replaced by Himmler) hypocrisy for sure!

Absolutely!

DeleteThe Nazis pursued the eradication of homosexuality for two primary reasons. The first rationale is succinctly encapsulated in Heinrich Himmler's introduction to his 1937 Bad Tölz speech on homosexuality. In this address, he elucidates why male homosexuals were perceived as a significant threat to the German nation:

(See below)

1 - To wage and triumph in a war, a nation requires soldiers (men). Himmler's 1937 speech serves as further evidence that the Nazis harbored ambitions of global dominance

Delete"According to the latest censuses, we must have sixty-seven to sixty-eight million inhabitants in Germany, or thirty-four million male individuals, taking a round number. We therefore have approximately twenty million men of childbearing age (this refers to men over sixteen years old). There may be a million error, but it doesn't matter.

"If I assume that there are one to two million homosexuals, that means that 7 to 8% or 10% of male individuals are homosexual. And if the situation does not change, it means that our people will be wiped out by this contagious disease. In the long term, no people could resist such a disruption of their lives and their sexual balance.

"If you take into account (which I have not yet done) the two million men who died in the war and if you consider that the number of women remains stable, you can imagine how these two million homosexuals and these two million deaths (so four million in total) are unbalancing sexual relations in Germany: this will cause a catastrophe.

"There are people among homosexuals who take the following point of view: "What I do is no one's business, it's my private life." But it is not about their private life: the area of sexuality can be synonymous with life or death for a people, with world hegemony or with the reduction of our importance to that of Switzerland. A people who have many children can claim world hegemony, world domination. A people of noble race who have very few children have a ticket to the afterlife: it will no longer matter in fifty or a hundred years, and in two hundred or five hundred years it will be dead."

The above text has been Google translated from the German.

2 - From fascination to persecution

ReplyDeleteNazi art proves to be one of the keys to analyzing and understanding the National Socialist regime. In any case, it allows us to understand the fascination exerted by homosexuality on the Nazis and its turn into a merciless persecution.

In the aftermath of the German defeat of 1918, the dream of a return to the state of nature swept across the devastated country, which aroused numerous attempts to resurrect pre-Christian Germanic cults. A mythical glorification of “virility”, a relegation of women to the church, the kitchen and the nursery (Kirche, Küche, Kinder, the 3 “Ks”) slyly marked the paths to a certain ambiguity regarding homosexuality.

The German Social Democratic Party (SPD), the leading German political party under Weimar, supported the homosexual struggle but in a muted way. The German Communist Party asserted itself as the best defender of the homosexual cause.

(...)

Hysterical homophobia, championed by Heinrich Himmler, was not the initial position of the National Socialist Party, even if its ruthless internal logic led it to radical hostility towards homosexuality.

Nazi mythology and art fit exactly into this perspective. The myth of Arianity will serve to exalt the “new man” whose attributes are virility and camaraderie, strength and valor. The “new race of Lords” is distinguished by its robustness and physical health, beauty and strength. Arno Breker and Joseph Thorak derive beauty from bodily perfection to the exaltation of brutal force through muscular excess and the hardness of facial features printed in stone.

Homoeroticism is more than suggested by Nazi art which advocates the cult of the male body, naked, oiled and muscular, offered in suggestive athletic poses, which can only arouse the spectator's desire for such a perfect body - no without admiration and envy being mixed with more troubled feelings that are strengthened by incessant calls for “virile camaraderie”.

(...)

The cinematographic production of the Third Reich is very marked by homoeroticism. Male friendship, virile beauty, heroism are constants. The ardor of youth, its enthusiasm, its independence are the regenerative forces of the German nation, but all this is undermined by a devastating misunderstanding.

A "fashionable homosexuality" could have appeared, and even if a certain "homosexual community" mixed social classes and defied the categories in which we like to classify homosexuals, these, even in the affirmation of their differences which they wanted to see recognized, were repugnant to this reduction of the originality of each person disappearing, melting into a uniform mass, the ultimate goal of the Nazi system.

(...)

The overinvestment in virility, by which Germany was supposed to win the war, exaltation of violence, of brutality refused by some, is for others a call to pleasure. The theories of torch bearers, wounded warriors and other naked colossi with hypertrophied muscles were for some symbols of victorious heroes, examples to be reproduced through self-sacrifice. Misinterpretation and misunderstanding were not be able to withstand the blows of National Socialism.

As soon as Hitler came to power, homophobic persecution began, and it should be noted that it was immediately accompanied by a sadism that can only be understood as the inverted admission of the fascination exerted by homosexuality on those in power, and a means of clearing oneself, of relieving oneself of guilt through crime of any shame of unfulfilled desire. Nazism's fight against homosexuality was merciless.

(Source: From Fascination to Persecution, Blaise Noël, 2000.

The above text has been Google translated from the French.

Really interesting and fascinating article. I didn't know much about the circumstances of gays in Germany before the Holocaust. Thank you for sharing this.

ReplyDeleteThank you for your comment.👍

Deleteet pourtant quand on voit ou revoit les images de Visconti "Les Damnés" il y a bien sûr le massacre des orgiaques, mais aussi une descente ou une apologie de la différence dans le personnage du fils trans -repenti?-

ReplyDeleteLa fascination/répulsion évoquée plus haut est à l'origine de certains égarements qui font confondre victimes et bourreaux. Il y a dans l'iconographie nazie un homoérotisme indiscutable, mais cet homoérotisme s'est souvent terminé à Sachsenhausen (proche de Berlin), Buchenwald ou Dachau.

Delete